What Is Galvanic Isolation and Why Does It Matter for Audio?

The science behind eliminating ground loops and electrical noise from your digital audio chain.

Every so often, someone in an audio forum asks why their expensive new DAC sounds "hazy" or has a faint hum they can't track down. Nine times out of ten, the answer has nothing to do with the DAC itself. It's about what's connected to it—and whether there's a direct electrical path between components that shouldn't be sharing electrons.

The Basics (I Promise to Keep It Simple)

Galvanic isolation means complete electrical separation between two circuits. No shared ground wire. No common power supply. No conductive connection at all.

The name comes from Luigi Galvani—yes, the guy who made frog legs twitch with electricity back in the 1780s. In his honor, we call electrical current flow "galvanic." So galvanic isolation just means: stopping that current from flowing where it shouldn't.

But here's the clever part. Signals still need to get across. You can't just cut all the wires. So isolated circuits pass information using magnetic fields (transformers), light (optocouplers), or capacitive coupling—methods that transfer data without any metal touching metal.

Why Your Audio System Has a Ground Problem

In theory, every "ground" connection in your system should be at exactly zero volts relative to every other ground. In practice, this almost never happens.

Your streamer plugs into one outlet. Your DAC plugs into another. Your amplifier uses a third. Each outlet's ground has a slightly different potential because of wiring resistance, other loads on the circuit, and the general chaos of household electrical systems. These differences are tiny—millivolts—but audio equipment is designed to hear tiny signals. That's literally the job.

When you connect two components with an audio cable, you're also connecting their grounds. Now current can flow between them—not because you want it to, but because physics demands that electrons move from higher potential to lower potential. This circular current path is a ground loop, and it adds noise to your signal.

Sometimes it's an obvious 60Hz hum (50Hz if you're in Europe). Sometimes it's subtler—a haziness, a loss of detail, a sense that the music isn't quite as clean as it should be. Paul McGowan at PS Audio has called this the "gray veil" that lifts when you properly address grounding in a system.

USB Made Everything Worse

Remember when audio was simple? Turntable to preamp to amp, all with nice isolated RCA connections? Those were the days.

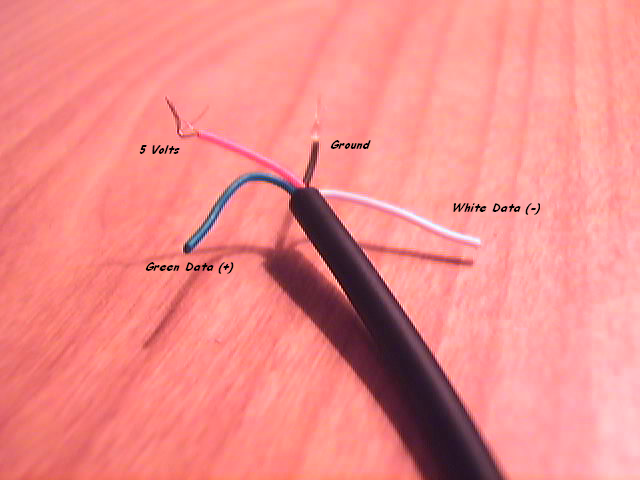

USB changed everything. Unlike dedicated audio connections, USB was designed for data transfer—keyboards, mice, hard drives. Audio was an afterthought. And USB has a fundamental problem for audio: it includes both a ground connection AND a 5V power line.

That power line is convenient—it means your DAC can be powered by your computer without a separate power supply. But it's also carrying all the electrical noise from your computer's switching power supply, its digital circuits, and whatever else is going on inside that noisy box.

Thorsten Loesch, the engineer behind iFi Audio's products, has written extensively about this. In a USB connection, noise doesn't just travel on the power line. It affects the data lines (D+ and D-), and it absolutely travels through the ground wire. Even if you use a USB cable that cuts the power line, you've still got ground-coupled noise.

For computers and printers, none of this matters. For audio? It matters a lot.

The Raspberry Pi: A Worst-Case Scenario

I love Raspberry Pi for audio streaming. The flexibility, the software options, the price—it's amazing what you can do with a $35 computer. But from an electrical noise perspective? It's a nightmare.

The Pi has switching voltage regulators that create high-frequency noise. It's got WiFi and Bluetooth radios broadcasting interference. The processor creates digital hash. All of this sits millimeters away from the GPIO pins that carry your audio signal or the USB port that connects to your DAC.

Connect a Pi directly to a sensitive DAC, and all that noise comes along for the ride. Some DACs reject it better than others, but you're always starting from a compromised position.

How Galvanic Isolation Solves This

Put a galvanic isolator between your source and your DAC, and you break the electrical connection. The grounds are no longer linked. Current can't flow between them. Ground loops become physically impossible.

The signal still gets through—either via a small isolation transformer that couples the data magnetically, or through optocouplers that convert electrical signals to light and back. But the noise, the ground currents, the power supply garbage? Blocked.

PS Audio's Paul McGowan has a good analogy for this. He compares it to passing a note through a window. The information gets through, but the air on one side (with all its smells and temperature) stays separate from the air on the other. You get the message without the baggage.

What the Skeptics Say

Look, I'm not going to pretend galvanic isolation is universally praised. Some engineers argue that if your system is properly designed, you shouldn't need it. Digital audio is digital, they say—ones and zeros aren't affected by a bit of ground noise.

They're technically right about the data. But they're missing something important: timing.

Digital audio relies on precise timing. The clock that synchronizes when each sample is read needs to be stable. Noise on power and ground rails can affect clock jitter—tiny variations in timing that, accumulated over millions of samples per second, affect how your DAC reconstructs the analog waveform.

Is this audible? Honestly, it depends on your system, your ears, and how much noise you're dealing with in the first place. But the engineers at companies like PS Audio, Chord, and dCS clearly think isolation matters—they build it into their high-end products.

The Practical Reality

Here's my honest take after years of messing with this stuff:

If you're running a simple system—one source, one DAC, everything plugged into the same power strip—you might not have a ground loop problem. Galvanic isolation might not make an audible difference.

But if you're using a computer or Raspberry Pi as a source? If you've got components spread across multiple outlets? If you've ever noticed a faint hum or wondered why your system doesn't sound quite as clean as it should? Galvanic isolation is worth trying.

For my Pi-based streaming setup, isolation wasn't optional—it was mandatory. The improvement wasn't subtle. That "gray veil" Paul McGowan talks about? Gone. The background got blacker. Details I hadn't noticed before became obvious.

Your mileage may vary. But in my experience, keeping the Pi's electrical chaos completely separated from the audio path made more difference than any other single upgrade I've tried.

Implementation Options

If you want to add galvanic isolation to your system, you have a few choices:

- Inline USB isolators: Products like the iFi iGalvanic or Intona isolators sit between your source and DAC. Convenient, but you're adding another box and cable to the chain.

- DACs with built-in isolation: Some high-end DACs include isolation on their USB input. Check the specs—it's not universal even at premium price points.

- Integrated streaming solutions: Purpose-built audio streamers often include isolation as part of their design, addressing the problem at the source rather than patching it downstream.

For Raspberry Pi users, the choices are more limited. Most DAC HATs connect directly to the GPIO with no isolation. USB isolators work but add complexity. What you really want is a solution designed specifically for Pi audio that includes isolation from the start.

The DSD Bridge includes 2500Vrms galvanic isolation between your Pi and DAC—true electrical separation where it matters most.

Learn About the DSD Bridge

Comments

Be the first to comment on this article.